november 29, 2022 - Francesca Minini

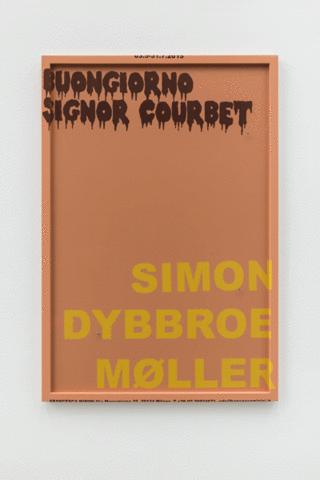

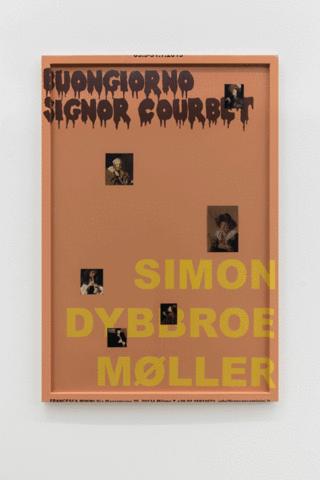

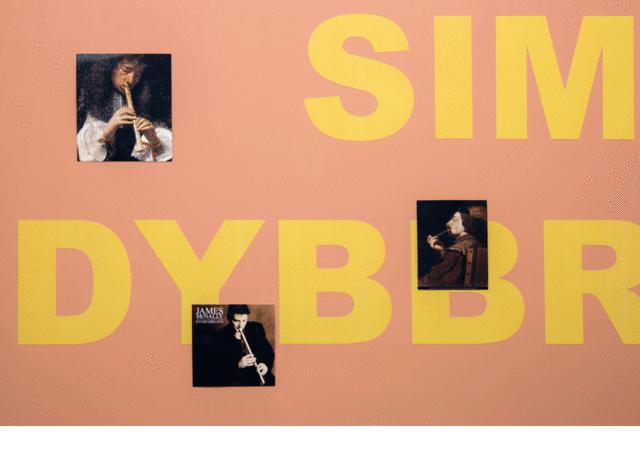

Simon Dybbroe Møller: What Do People Do All Day

What do #people do all day? The first thing that comes to mind is work. We tend to assume that a job defines us by what we do. Simon Dybbroe Møller's eponymous video series considers just this. In episode 1, Everyone Is a Worker, an exhausted looking woman plies viewers with questions like "Do you understand futures trading?" "Do you know where the apples in your apple pie come from?" or "Do you know who fixes the clocks?" Her tone is vaguely accusatory but also rhetorical. We don't expect a "yes" or "no" answer because we seldom give these things a second thought. All the while, the interrogator is in motion, slowly rotating. She appears clad, variously, as a waiter, a doctor, a farmer, or a mechanic. "Maybe there are clothes you have to wear." "Do you have a job?"

Work conventionally defines purpose in contemporary life. Yet, virtues of productivity aside, work carries the onus of entry into a predetermined system of exchange, which measures your labor against things. And, despite your reduced status, you are also always something more.

Dybbroe Møller drew inspiration from Richard Scarry's classic book for children, also titled What Do #people Do All Day? The story Scarry tells is didactic, prompting young readers to consider how the society they live in actually works. The "people" in this narrative, the inhabitants of Busytown, are represented by animals. Scarry suggests that this network is all-inclusive: from the deer who farms, to the cat who sells groceries, to the rabbit who makes and repairs clothes, to the fox who makes metal tools. They all rely on each other. Everyone is a worker. In this peaceable kingdom, their connections to each other are direct and mutually supportive.

Yet, we no longer know where our apples come from or how to fix a clock, let alone how the futures market works. We buy and use things already there, merely choosing from various styles. We choose based on a compensatory sensibility: taste. We buy readymades, a term that intrinsically occludes labor. Moreover, the sheer scale of mass culture and its concomitant specialization render work more abstract and less knowable. Add capitalism to the mix, and material production becomes even more remote.

After the interrogator's questioning, Everyone Is a Worker cuts to erotic scenes of a youthful catholic priest making out with a woman who works in an Apple Store. All the while, a voiceover recounts exchanges in an idealized agricultural economy. Despite -- or perhaps because of -- its necessity, many equate work with drudgery. Eroticism, via excess and uselessness, offers an escape. If, like the priest, you transgress in the process, it feels even more liberating. At the very least, eroticism can break up the monotony of work.

By forcing office workers to work from home, the COVID pandemic eroded an otherwise clear distinction between work and leisure. Mothers, and some fathers, juggled their professional lives with childcare.

Rules became lax. Some watched porn and played video games when they were supposed to be working. Others did two jobs at the same time, effectively doubling their earnings. #people spent the day in pajamas. It became harder to get things done. Employers began conducting online surveillance to crack down on bad behavior. In turn, metrics became even more overbearing.

Under these conditions, some sought the goal of early retirement: make your money while you're young and spend the rest of your life enjoying it. However, leaving the workforce isn't a blessing for all. Many experience a loss of self-worth and find themselves drifting or going through the motions of daily life: some, but not all.

Finally, the most overlooked demographic comprises those who cannot find a job, those who are unable to work, and those who are unhoused. In economic calculations, this group registers as a loss. Marx categorically dismissed them as lumpen proletarians lacking definition and political agency. Yet here, the fundamentals of life assert themselves solely for their own sake. As automation and technology efficiency make increasing numbers of jobs redundant, this condition comes to the fore. Accordingly, a guaranteed universal income becomes less a utopian aspiration and more a social mandate.

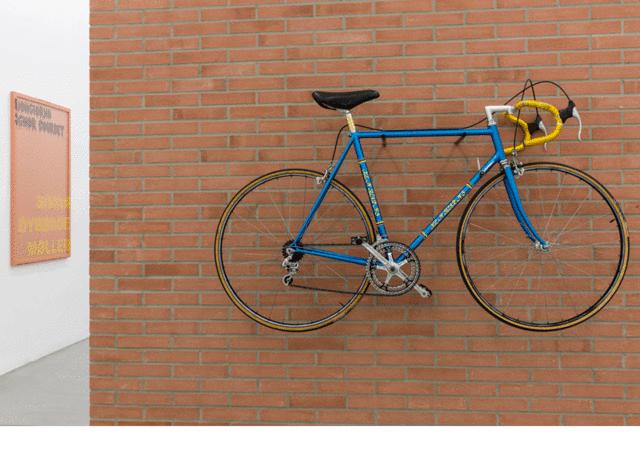

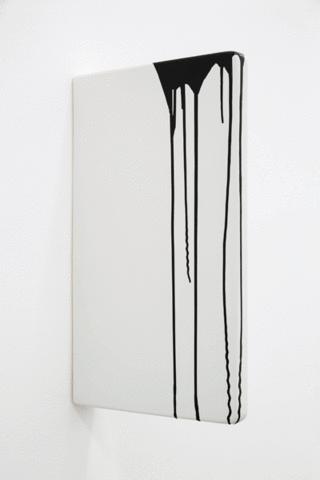

This #show marks the premiere of the final and conclusive episode of Dybbroe Møller’s mini-series. The New Family will screen alongside the three previous episodes: Everyone Is a Worker, Building a New Road, and Making Water Work. In his script for the first segment, Møller notes, "The first film ever shown was of workers leaving the factory." The entire series montages together seemingly disparate themes and references, ranging from rotating, frozen figures that suggest reification to the hippie ideal of nudity as innocence. From the postproduction of highly stylized digital footage to cinema verité. From Naked When You Come by the 60ies boyband The Lollipops to Gustave Courbet’s furious refusal to accept a national award to Elio Petri's 1971 movie, The Working Class Goes to Heaven.

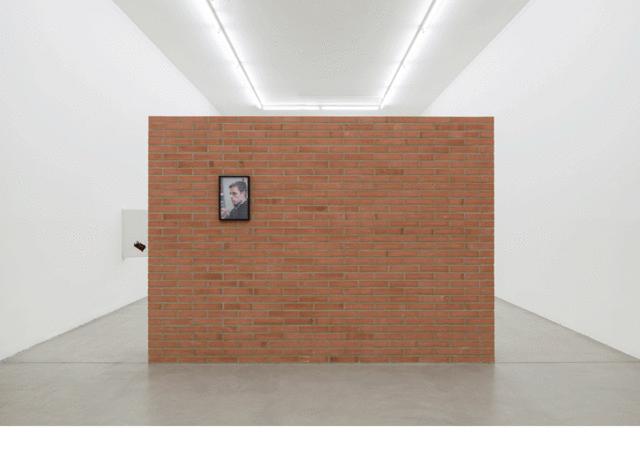

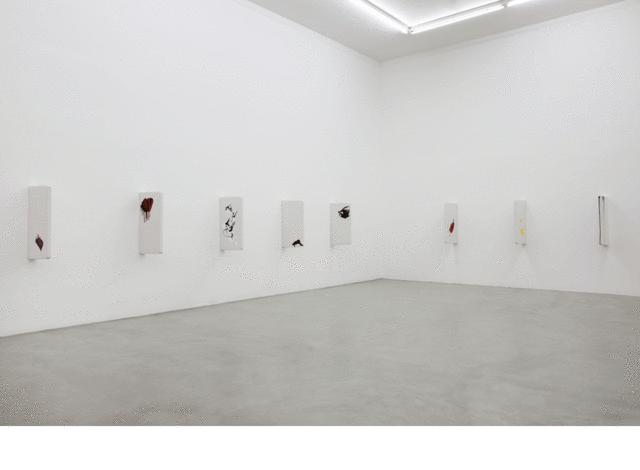

Instead of a single-channel presentation, Møller will #show the series in the form of a site-specific installation. Using a custom app, the episodes will be streamed on every available screen, from iPhones and iPads to flatscreens, laptops and desktops, whenever a visitor enters the gallery. This interrupts the flow of the gallery's office work, rendering the employees temporarily superfluous. It also calls into question the normative categories of art production. Is the artwork an autonomous entity? Or is its definition sustained by the bureaucratic apparatus in which it is embedded? Is the viewer also a worker? And, if so, how do we assign value to looking at art?

In the final scene of The New Family, the narrator, the actor Stacy Thunes, returns (nominally) as herself. She answers the camera at the door of her Berlin apartment, clad in a bathrobe, her hair still wet from the shower. She paraphrases Courbet, declaring: "When I am dead let this be said of me: 'She belonged to no school, to no church, to no institution, to no academy, least of all to any régime -- except the régime of liberty." After this, she slams the door on the camera. Here, perhaps, we are left to wonder who is the more potent realist, Gustav Courbet or Richard Scarry? Isn't the social construction of reality (which we casually consider reality per se) always bound up with the axiomatic institutions of language, exchange, production, and reproduction? The challenge, then, is to grasp what that is and, otherwise, what it might be.

Italian

Italian  Share

Share Share via mail

Share via mail  Automotive

Automotive Sport

Sport Events

Events Art&Culture

Art&Culture Design

Design Fashion&Beauty

Fashion&Beauty Food&Hospitality

Food&Hospitality Technology

Technology Nautica

Nautica Racing

Racing Excellence

Excellence Corporate

Corporate OffBeat

OffBeat Green

Green Gift

Gift Pop

Pop Heritage

Heritage Entertainment

Entertainment Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness