june 10, 2019 - Centro Pecci

'Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today' at Centro Pecci, Prato

Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today

June 07—October 06, 2019

an exhibition by the Vitra Design Museum and ADAM – Brussels Design Museum

Centro per l’arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci is delighted to present Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today, an exhibition produced by the Vitra Design Museum and ADAM – Brussels Design Museum that arrives at Pecci as the only Italian venue. The polyhedral and multidisciplinary project, with a specific focus on architecture and design, represents once again the attention of the Centro to the many languages of contemporaneity, and the more recent aim toinvestigate the non-conventional areas of knowledge to collect and deepen the testimonies of counter-culture.

The opening night, with free entrance from 6.00 pm, includes from 10.00 pm in the museum’s open-air theatre C2C Soundsystem: a selection by Club To Club, the famous festival of avant-pop and electronic music founded in 2002 in Turin which has become a point of reference in the international panorama of avant-garde music.

The opening of Night Fever is also an opportunity to visit the recently inaugurated exhibitions: Wiltshire Before Christ, a project by Aries, Jeremy Deller and David Sims (open until July 21, 2019) and Rirkrit Tiravanija. Tomorrow Is the Question (open until August 25, 2019), and to retrace the history of the first thirty years of #centropecci through The Museum Imagined - Timeline, an exhibition that tells the story of the protagonists of #contemporaryart through exhibitions, concerts, exhibitions, festivals, workshops and talks hosted by the museum in these past three decades.

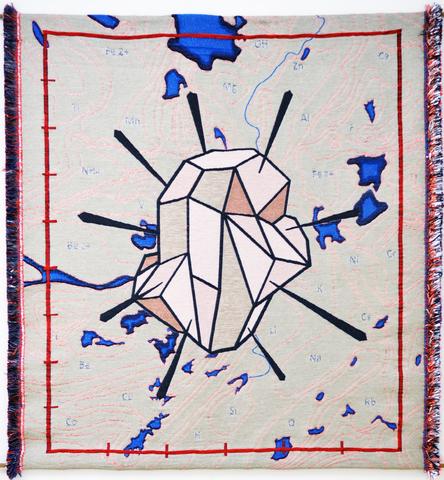

Nightclubs are epicenters of contemporary culture. During the 21st century they questioned the prefix codes of collective leisure and allowed to experiment alternatives lifestyles. In nightclubs we see the most advanced design, graphic and fashion, lights, sound and special effects manifest as one to create a modern Gesamtkunstwerk.

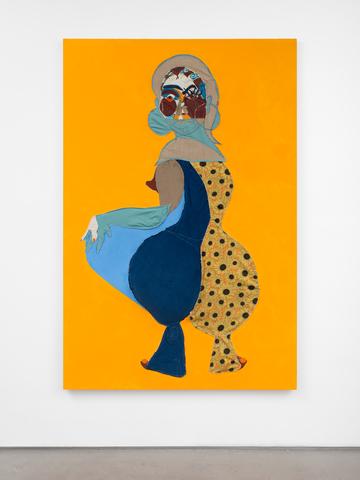

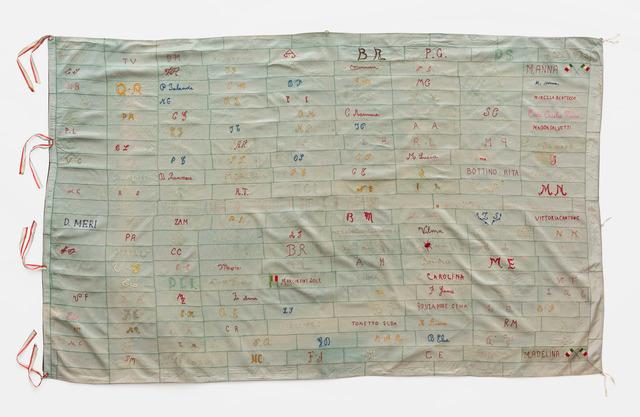

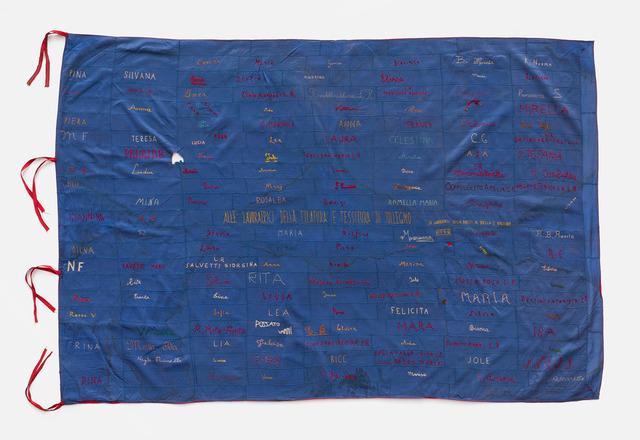

Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today considers the history of clubbing, with examples ranging from Italian clubs of the 1960s, created by the protagonists of Radical Design, to the legendary Studio 54 created by Ian Schrager in New York (1977-80); from the Les Bains Douches by Philippe Starck in Paris (1978) to the more recent Double Club in London (2008), by the German artist Carsten Höller for Fondazione Prada. The exhibition features films, vintage photographs, posters, clothing and artworks, as well as a series of light and sound installation, which will take visitors on a fascinating journey through a world of glamour, subcultures and in search of the night that never ends.

The exhibition follows a chronological itinerary that begins in the 1960s, exploring the emergence of nightclubs as spaces where for the first time the act of dancing is transformed in a collective ritual officiated in a fantastic world of lights, sounds and colors. Electric Circus (1967), designed by architect Charles Forberg and renowned graphic designers Chermayeff & Geismar, was a beacon of New York subculture, which influenced many clubs in Europe thanks to its multidisciplinary approach, including Space Electronic (1969) in Florence. Designed by the collective Gruppo 9999, this was one of several nightclubs associated with Italy’s avant-garde Radical Architecture. The exhibition also features Piper in Turin (1966), designed by Giorgio Ceretti, Pietro Derossi and Riccardo Rosso as a multifunctional space with a modular interior suitable for concerts, happenings, experimental theatre, and dancing. Gruppo UFO’s Bamba Issa(1969), a beach club in Forte dei Marmi, was another highly histrionic venue, its themed interior completely overhauled for every summer of its three years of existence.

With the rise of disco in the 1970s, club culture gained a new momentum. Dance music developed into a genre of its own and the dance floor emerged as a stage for individual and collective performance, with fashion designers such as Halston and Stephen Burrows providing the perfect outfits to perform and shine. New York’s Studio 54 (1977), founded by Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell and designed by Scott Bromley and Ron Doud, soon became a celebrity favorite. Only two years later, the movie Saturday Night Fever marked the apex of Disco’s commercialization but the origins of disco music are not mainstream at all: born in clubs frequented by LGBTQ+, black and Latino communities, marginalized by the white and heterosexual majority, the disco scene developed in tandem with a huge social and political movement. With disco as its soundtrack, Paradise Garage (1979) was the first gay club to break racial and sexual discrimination rules, prompting counter-movements as the Disco Demolition Night in Chicago (1979), where a box of disco records was blown up in a Chicago baseball field, representing reactionary right-wing feelings characterized by homophobia and racism.

Around the same time, places in New York’s thriving nightlife like the Mudd Club (1978) and Area(1983) offered artists new spaces merging the club scene and arts and launched the careers of artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. In early 1980s London, meanwhile, clubs like Blitz and Taboo brought forth the New Romantic music and fashion movement, with wild child Vivienne Westwood a frequent guest at Michael and Gerlinde Costiff’s Kinky Gerlinky clubnight. But it was from Manchester where architect and designer Ben Kelly created the post-industrial cathedral of rave, The Haçienda (1982), that clubbing, through Acid House, conquered the UK. House and Techno were arguably the last great dance music movements to define a generation of clubs and ravers. They reached Berlin in the early 1990s just after the fall of the wall, when disused and derelict spaces became available for clubs like Tresor (1991); more than a decade later, the notorious Berghain (2004) was established in a former heating plant, demonstrating yet again how a vibrant club scene can flourish in the cracks of the urban fabric, on empty lots and in vacant buildings.

Developments have become ever more complex since the early 2000s. On the one hand, club culture is thriving and evolving as it is adopted by global brands and music festivals; on the other, many nightclubs have been pushed out of the city or survive merely as historical monuments and modern ruins of a hedonistic past. At the same time, a new generation of architects is addressing the nightclub typology. The architectural firm OMA, founded by Rem Koolhaas, has developed a proposal for a 21st-century Ministry of Sound II for London, while Detroit-based designers Akoaki have created a mobile DJ booth called The Mothership to promote their hometown’s rich club heritage.

Completing the chronological structure of the exhibition, a music and light installation created specially by exhibition designer Konstantin Grcic and lighting designer Matthias Singer offers visitors a silent disco bringing them within the dynamic history of club culture. Additionally, a display of record covers, ranging from Peter Saville’s designs for Factory Records to Grace Jones’s album cover Nightclubbing, underlines the significant relationships between music and design in club history since 1960 to today.

Represented artists, designers and architects (selection):

François Dallegret, Gruppo 9999, Halston, Keith Haring, Arata Isozaki, Grace Jones, Ben Kelly, Bernard Khoury, Mark Leckey, Miu Miu, OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture), Peter Saville, Studio65, Roger Tallon, Andy Warhol.

Represented clubs (selection):

The Electric Circus, New York 1967; Space Electronic, Firenze 1969; Il Grifoncino, Bolzano 1969; Studio 54, New York 1977; Paradise Garage, New York 1977; Le Palace, Parigi 1978; The Saint, New York 1980; The Haçienda, Manchester, 1982; Area, New York 1983; Palladium, New York 1985; Tresor, Berlino 1991; B018, Beirut 1998; Berghain, Berlino, 2004.

Curators:

Jochen Eisenbrand, capo-curatore; Meike Wolfschlag e Nina Steinmüller, assistenti curatrici (Vitra Design Museum) | Catharine Rossi, co-curatrice (Kingston University London) | Katarina Serulus, co-curatrice (ADAM – Brussels Design Museum).

Elena Magini, associate curator (Centro Pecci)

Italian

Italian  Share

Share Share via mail

Share via mail  Automotive

Automotive Sport

Sport Events

Events Art&Culture

Art&Culture Design

Design Fashion&Beauty

Fashion&Beauty Food&Hospitality

Food&Hospitality Technology

Technology Nautica

Nautica Racing

Racing Excellence

Excellence Corporate

Corporate OffBeat

OffBeat Green

Green Gift

Gift Pop

Pop Heritage

Heritage Entertainment

Entertainment Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness